Huge spending by governments kept the world economy afloat during the pandemic as officials mobilized a fiscal response not seen since World War Two to bolster household incomes and give businesses a fighting chance to survive the health crisis.

But the resulting nearly $300 trillion pile of debt held by governments, businesses, and households will leave many countries with vulnerable finances and weigh on efforts to address urgent challenges such as climate change and aging populations.

Even as rich and poor governments take stock of battered finances, inflation is pushing central banks toward higher interest rates and a tightening of monetary policy which, for the indebted, can only make the math less favorable.

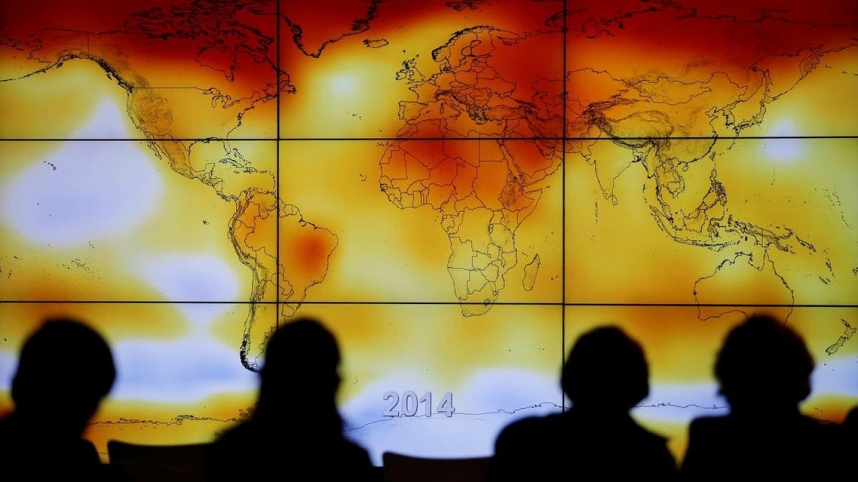

This month's Glasgow climate talks produced some new pledges by countries to reduce carbon emissions but left many questions unanswered about how commitments will be financed and put into practice.

According to the IIF (Institute of International Finance), global debt may just about have hit its peak from the pandemic and may fall slightly by year's end from the current $296 trillion.

But easing the reliance on carbon-based fuels and mitigating climate damage is expected to require massive public and private investment - on orders of $90 trillion by 2030, according to one World Bank estimate.

At this point, there's no global plan for how to underwrite it, and governments' share of climate investments will have to compete with social, health, and other spending priorities set to intensify because of demographic trends like aging populations.

The vast pandemic stimulus deployed by the rich world propped up their economies successfully and was also sustainable in a landscape dominated by low or near-zero interest rates. But as the cycle switches to policy tightening, this will mean higher interest costs, higher risk of possible debt crises in emerging markets, and less capacity to meet climate goals.